Tariff data from 452 cities across the world collected in the 2017 Global Water Tariff Survey by Global Water Intelligence (GWI) shows water and wastewater prices are rising, with an average increase of 3.91% worldwide. The global average was found to be $2.06/m3- with South Asia having the lowest average prices ($0.14/m3) and Denmark the highest ($7.07/m3). The trend is not a new one, and it’s especially obvious in places such as the U.S, where the constant compound annual growth rate of water prices has been 5% for the past 5 years.

A great example of the American predicament is Chicago, where the water rates have doubled over the past five years according to a recent report by Circle of Blue. “The new revenue will help the city to double the rate at which it replaces old water pipes,” is the reason given for the steep prices, proclaimed by water providers in Chicago and everywhere else. The Water & Sewer Authority (PWSA) of Pittsburgh, where tariffs have increased 18% in 2017, intends to use the money to fund the replacement of ageing pipes dating back to the pre-Civil War period and to upgrade outdated computer systems. GWI claims these are also the likely reasons for the global phenomenon.

Upgrades and improvements such as the ones in Pittsburgh, while no doubt crucial to ensure water supply and quality, often meet public resistance. Already burdened with taxes, citizens often raise their voice in protest of having to pay even more for a product that is considered a basic human right: water. And although on a theoretical level a clean supply of water is not considered a luxury- for many it is. Not only for people in countries where water is scarce, but now also for modern water utilities who are expected to provide a better product at the same low price. To meet modern standards utilities need a better infrastructure and the newest technology- all of which cost a pretty penny. To cover the expense, the public is used as a monetary resource: but should it?

Singapore is another example of the same method. Aiming for water independence by 2060, the country is now dedicated to research and innovation investments in the water sector- thus increasing tariffs for the first time in 17 years. Over the next two years Singapore water prices are expected to rise by 30% in order to meet the 85% independency goal set by PUB (Public Utilities Board). With PUB subsidizing draining and sewage activity the prices in Singapore remain relatively low compared to Europe or the US, but with PUB’s own investment in the endeavor estimated to be around $4 billion the hiking prices raise the same question they do everywhere else- who, exactly, should be expected to pay for our water?

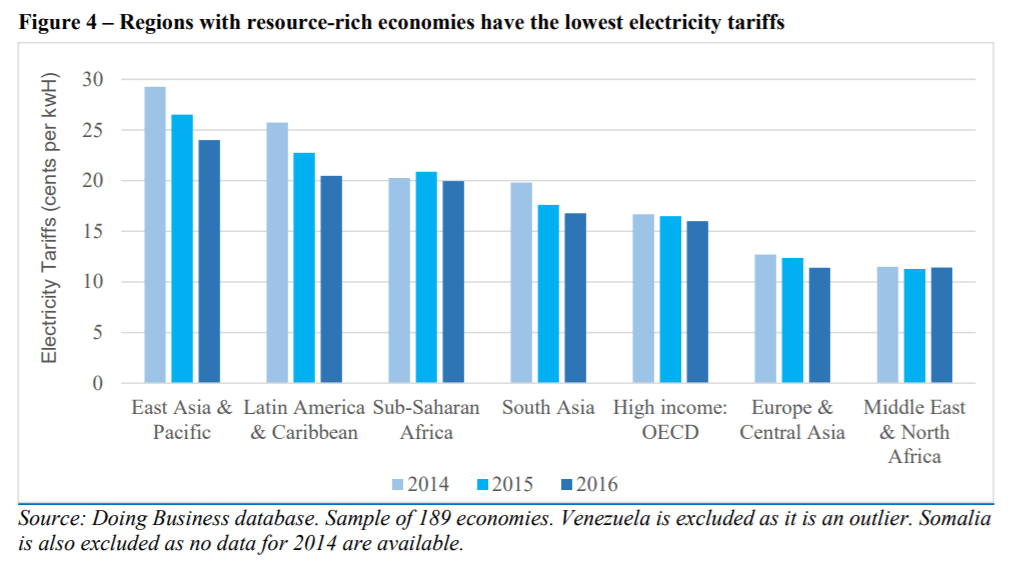

The answer, as we can all see in our own bills, seems to be the consumer. It’s a curious solution when compared to the energy sector, where the tariff growth rate has been stagnant. In developed countries a steady supply of electricity is a basic requirement, yet unlike water electricity prices have been dropping in Asia and Europe in the last three years, while in America they’ve stayed pretty much stable. Both the water and the energy market have been rapidly developing where it comes to technology- and both require money to continue to do so.

And yet, it’s the water sector which cannot manage resources well enough, thus requiring additional outside funds. In that regard Israel is functions as anomaly – a country where water prices in the last 5 years have dropped 30% ($1.86/m3, well under the global average). The current situation everywhere else, however, paints the future of water in uncertain tones: will prices continue rising indefinitely to cover up the costs of regular maintenance and necessary development or will the uproar birth a more efficient business model?

Sources:

About GWI’s Survey

Chicago’s predicament

Singapore’s tariff changes